Unlike virtually all other photographers who saw themselves as artists, and were seeking the attention of the museum establishment in the middle of the twentieth century, Richard Avedon was not a lone individual with a camera and a darkroom. He was rather the epicenter of an organization that was a whirlwind of carefully selected professionals and friends that spewed out photographs, both personal and commercial, sometimes several times a day, each meticulously constructed and imbued with his own highly distinct imprimatur. He was acutely aware that the images he was creating were much the better for incorporating the skills of others, be those skills basic and easily replaced, or unique, indispensible, collaborative, and transformational.

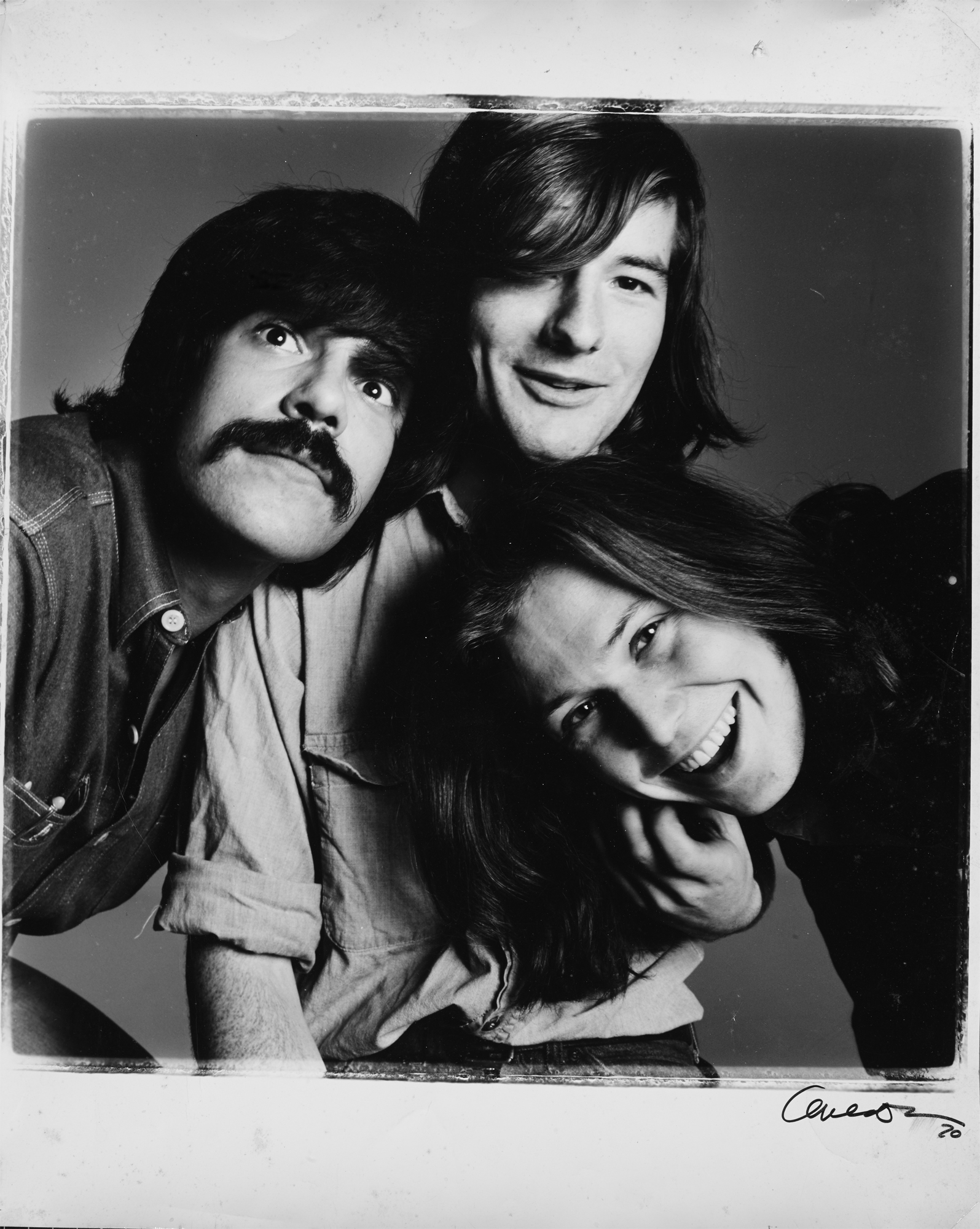

I was very briefly near the heart of this system, in the basic and easily replaced category, and on its periphery for much longer. Here I am as a studio assistant in 1970, in the middle of a triumvirate of the easily replaced.

But easily replaced does not mean unnecessary.

The only time I recall that Richard Avedon went somewhere entirely alone with the intention of taking photographs, he came back without photographs, since he had been unable to figure out how to get the film into the camera. But in that instance, what he was lacking was an assistant, not a collaborator.

So if we are going to have a discussion about Avedon the collaborator, we need to define for the purposes of that discussion, just what a collaboration is, and who is therefore a collaborator.

A person who writes the text accompanying a book of photographs or the person who designs that book or exhibition, is not necessarily a collaborator. If for example, the writer or the designer were not already involved when the photographs were being made, the product is not, in the terms of today’s conversation, a collaboration.

Thus, Truman Capote in Observations and James Baldwin in Nothing Personal are Avedon’s co-authors, they are not his collaborators.

On the other hand, when a significant portion of the essence of a work is done by more than one person—as in the case of Marvin Israel and Avedon’s first retrospective or Doon Arbus and The Sixties—it is a collaboration.

Of course that doesn’t make Avedon any less the auteur. No matter how the work is conceived, he is responsible for the execution, and no one collaborating with Richard Avedon was in any doubt that what they were working on was ultimately a project of his.

Marvin Israel, became the art director of Harpers Bazaar in 1961 after Avedon’s spectacular initiation at the magazine with Alexey Brodovitch, followed by a brief interval with the austere Henry Wolf that had left Avedon starved for a soul mate.

Avedon and Israel immediately entered into a collaborative relationship that continued, broken periodically by ferocious disagreements, until Israel’s death from a heart attack 23 years later, in 1984, in Texas where they were working together on the In the American West project.

Their iconoclastic and radical instincts played out at Harper’s Bazaar coincident with a brief period in the magazine world that allowed art departments to get away with murder.

Among the most notorious, in what was nominally a fashion story, they conspired together with Avedon’s friend, comedian Mike Nichols, on a parody of Paris Match’s coverage of the illicit, secret affair between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

Israel’s last hurrah after less than two years at the magazine was an Avedon cover picture that bore a striking resemblance to a glamorous portrait of the former Harper’s Bazaar fashion editor Diana Vreeland who had recently moved to arch competitor Vogue. Bazaar‘s editor Nancy White, always suspicious of Israel, believed the image to be even more scandalous than it was. Outraged, she confronted him, having assumed the model was actually a man. A furious argument ensued, vicious insults were thrown and Israel was fired.

But Avedon and Israel were already at work on the project that became the book Nothing Personal, intended to be a critique of the state of the nation during the civil rights movement.

For the part of the project involving the American south, they needed a guide, someone who could choose subjects and who had access to that closed, and often hostile society.

Israel introduced Avedon to Marguerite Lamkin, with whom he had worked at Seventeen magazine. She was a well-born and well connected southerner who had frequently been hired as a voice coach to teach actresses playing southern women, most notably Elizabeth Taylor in the movie of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, how to sound like her.

Miss Lamkin, on whom it is widely believed Truman Capote based the character of Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, agreed to use her connections to provide Avedon with subjects in the south. In the event, many photographs in Nothing Personal were taken on the resulting road trip, which ended abruptly after a telephoned death threat to Avedon in his motel room. Here is Marguerite Lamkin speaking about that trip:

Marguerite, whose charm to this day remains irresistible, subsequently made all the contacts, connections and appointments for virtually the entire book.

I once asked Israel why he didn’t have a copy of Nothing Personal in his studio, and he replied that he had had a huge fight with Avedon just before it was published and never got a copy. He added that he always seemed to have a huge fight with Avedon at the end of every project….The singular exception of course, was the project that was in progress when he died.

After the publication of Nothing Personal, which was eviscerated in the New York Review of Books, five years elapsed before Avedon embarked on another project.

Israel and Avedon (ever his own fiercest critic,) had together concluded that a principal weakness of the photographs in Nothing Personal had derived from the photographer’s consummate skill with the Rolleiflex camera, which they both felt encouraged him to effortlessly slip into a slick satirical or sentimental mode of image making that he actually fundamentally disapproved of.

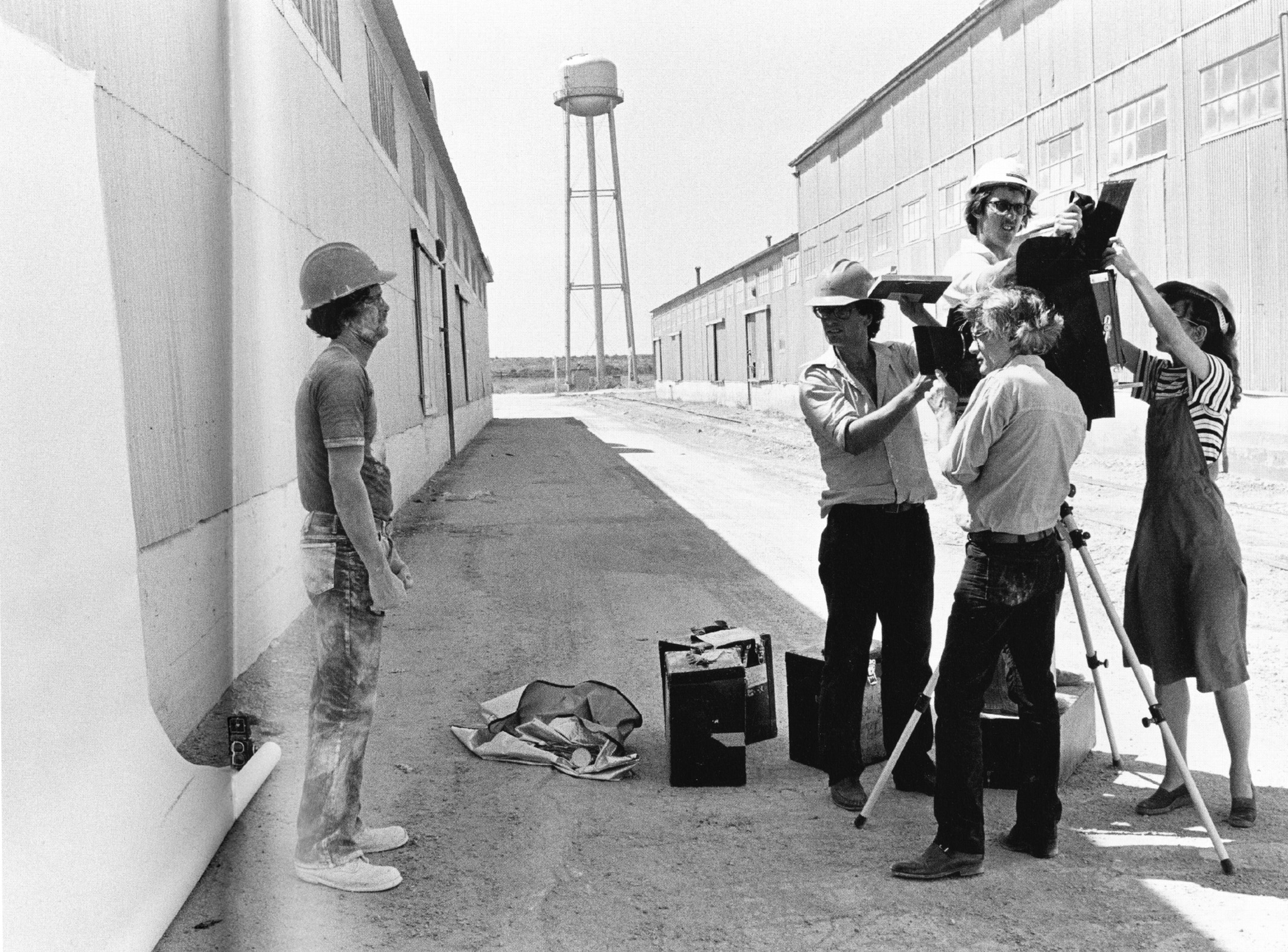

For Avedon’s next project Israel proposed the use of a huge, specially built, deliberately ungainly, non-standard camera in order to solve the problem.

Avedon settled for an 8x10 (20cm x 25cm) camera, which had the desired effect of imposing discipline by immobilizing both subject and photographer.

Israel had also suggested to Avedon that to give the nascent 60’s project form and direction that he should hire Doon Arbus, Diane Arbus’s daughter, to schedule the subjects for the photographs. The project hoped to document the principal players in the anti-war movement from Yippies to rock stars, for a show and book.

At 24 years of age, Doon’s writing was already being noticed in the magazine world. Avedon took the advice, interviewed and hired her, and in no time Doon was managing the project, was present at every sitting, and thanks significantly to her listening skills, was conducting all the interviews, often alone, with the subjects.

As the project evolved, it took the form of mounted 8x10 inch contact prints with the subject’s interview glued on the back.

The two shared a long desk facing a wall of the pinned up contact prints in

Avedon’s personal office at the studio, where neither of them even had to look up in order to continue a conversation that once begun, continued with occasional interruptions, for the next thirty years.

If you are familiar with any of Avedon’s published writing or more likely his aphorisms on the subject of photography over that time, they were likely written either by Doon and Avedon together, or by Doon alone and subsequently edited together. In any event, the words that emerged spoke with what soon became a single consistent and unmistakable voice.

Thus “My photographs don’t go below the surface, I have great faith in surfaces, a good one is full of clues. Scratch the surface, and if you’re really lucky, you find more surface.” And, “A photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows he is being photographed, and what he does with that knowledge is as much a part of the photograph as what he is wearing and how he looks.” Also, “There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate, none of them is the truth.” All these and many other ideas emerged from the office with the long desk, and became via the mouthpiece of the auteur a significant part of his legend.

None of them would have been uttered as they were without Doon’s involvement, but it was Avedon who made the decision to embrace her and weave her into the various manifestations, personal and commercial, of his thing.

When I arrived to work at the studio in early 1970 the place was a hive of activity.

Bea Feitler, the co-art director of Harpers Bazaar with Ruth Ansel, both of whom had been Marvin Israel’s assistants at the magazine, was finishing up Lartigue’s Diary of a Century.

In addition to quantities of commercial assignments, Avedon was photographing, it seemed every day, cultural and political figures that Doon Arbus had found for his 60’s project, which was expected to become an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and a book.

Planning was also going on for a lengthy trip to Viet Nam, where the war was still very much being fought.

By the end of the year work was proceeding on the book Alice in Wonderland, about the founding of a company and its first production, a play that had tremendously engaged and excited Avedon. The book although entirely Avedon’s idea, was mostly text, written or edited by Doon, and although vibrantly and lavishly illustrated with photographs, Avedon’s name was last on the list of ten people credited with its creation.

Meanwhile, a very large show of photographs was being put together for the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, funded by the Dayton Hudson Company of Minneapolis, a commercial client of Avedon’s.

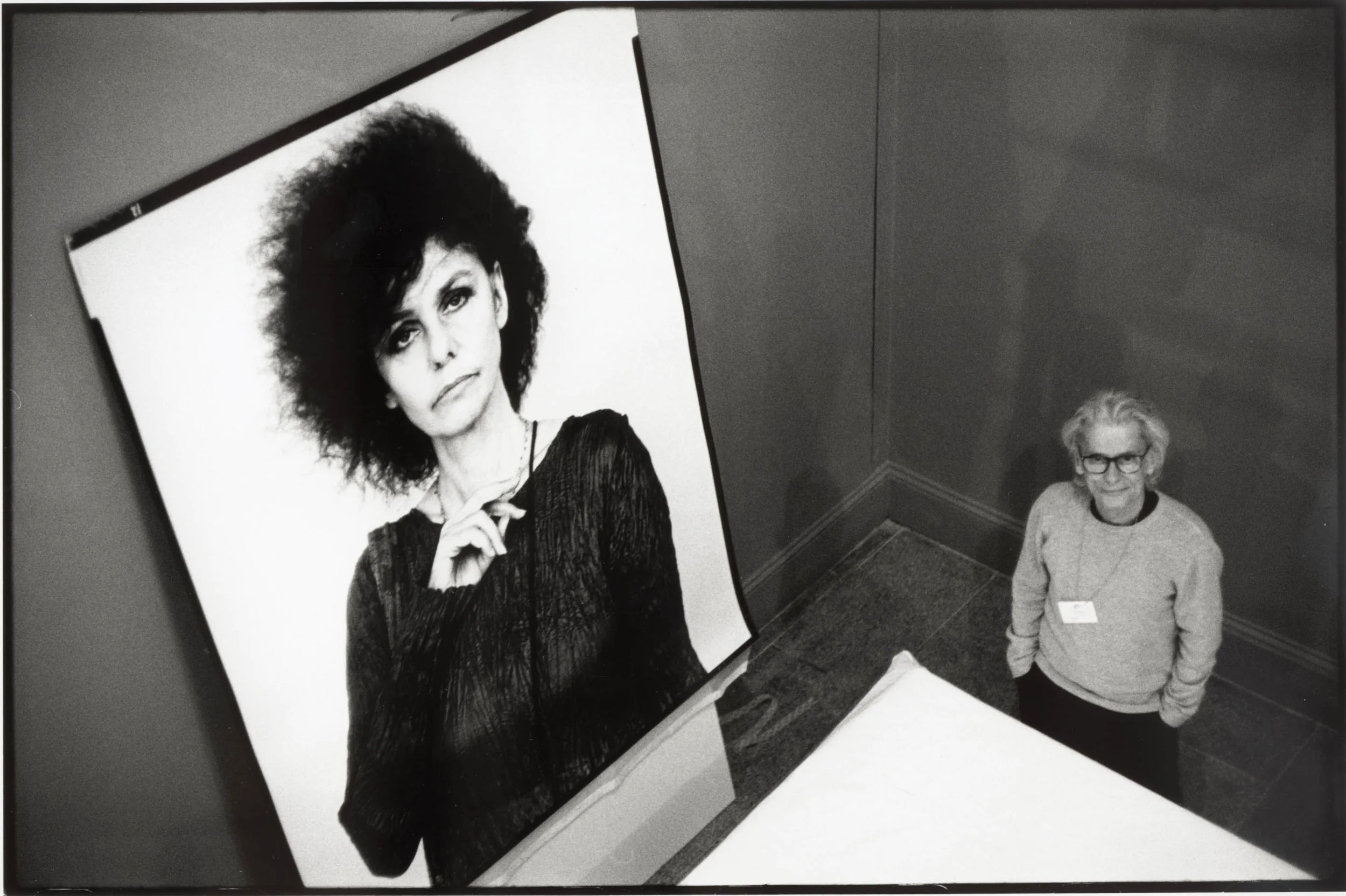

His next show was of portraits, at the Marlboro Gallery in New York as described here by Maria Morris Hambourg of the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

All of these projects, culminating as they did as books and exhibitions were conceived and executed as part of a decades long conversation within a small group friends. That conversation covered all forms of cultural life, political life as well as the connection of each of the participants to their own worlds and to the world they had created together and shared with each other. Avedon had managed to surround himself with people who took personal satisfaction from making his work better.

For the celebrations surrounding the opening of the Minneapolis retrospective, all the guests were given Avedon masks to conceal their identities. This picture may be a kind of metaphor for what I’m trying to say.

Obviously, the separate functions and activities of collaborators tend to have very indistinct boundaries, and the relative proportions of their collaborative input are by definition almost infinitely arguable. To attempt to define those boundaries is therefore simply a waste of time; the point is that unlike his peers, Avedon made a choice and a decision to collaborate.

What is impossible to divine is how his pictures and to a lesser degree his words evolved differently than might otherwise have been the case, when their principle creator was involved in decades long conversations about the photographs with intimates who appeared to all outside observers to be indispensable, by the mere fact of the ubiquitousness of their presence.

I am eager to make the distinction between relationships that are purely professionally symbiotic, and the intimate kind of bond that Avedon wove most particularly with Marvin Israel and Doon Arbus, and also with others such as Marguerite Lamkin, writers Renata Adler and Adam Gopnick and with Nicole Wisniak through her magazine Egoiste.

Richard Avedon just scooped up and pocketed the best and the brightest to help him achieve his ends. Renata Adler was introduced to Avedon when she was the first person Doon suggested that he should photograph for The Sixties project.

It will come as no suprise that in turn, she was the guiding intelligence behind the 1976 Avedon project “The Family” published in Rolling Stone.

Once his photographic output became primarily devoted to his personal work, and his support structure, built for a very successful commercial photography business, was left in place, the distinction between his comparatively massive modus operandi and that of the other significant photographers of the time, who were all fundamentally solitary practitioners, was dramatic.

The pattern never changed, it never seemed to occur to Richard Avedon not to throw his thoughts and ideas at his trusted insiders and see what bounced back at him, and then once embarked on a project, to keep them very close as it evolved.

I’m going to play two very short clips, first Owen Edwards, writing in The Village Voice. It is very easy in these conversations about photography to lose track of the fact that Marvin Israel was a very active and singular painter, whose work was too controversial to find general acceptance at the time.

It is worth mentioning that just being briefly in the presence of Richard Avedon was for most people an exhilarating experience. For years after I worked for him in London in 1968, I was boring anyone who would listen with stories about that experience and the fact that it had been the most exciting week of my life, and that, it turns out was a typical reaction. It is almost impossible to imagine that the center of such an energy field could be anything other than an entirely self generated force.

On the other hand, there are those, themselves targets of adulation, who understand that brilliance may conceal unheralded support.

When I approached Robert Frank in 2005 and told him I was making a documentary about Marvin Israel, his response was “What took you so long?” For Frank, it was a given that Israel’s influence was seminal to New York’s late mid-century photographers.

Here Frank is having the last word on what collaboration with Israel contributed to their work:

Israel knew “how to frame it, how to keep it, how not to fuck it up in some way.”

Probably no one, and certainly no one here today would ever dispute Richard Avedon’s brilliance, but in part it was sustained by his compulsion to surround himself with minds that kept teasing, provoking, goading and inspiring him to eternally continue to outdo himself.

Photographs by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation. Used by permission. Text and videos © Neil Selkirk.